Reviews

Please read my review in The Flame Here.

Artweek.LA

Other Visions, Other Venues: Two Indie Curatorial Projects in Los Angeles

By Betty Ann Brown

November 20, 2013

Betty Brown reviews two exhibitions in alternative spaces, one a private home, the other a storefront that serves primarily as a center for photographic education.

Historically, the display of art was controlled by wealthy and powerful non-artists and limited to specific institutional settings, whether churches, palaces, or Academic Salons. It was not until 1855 that French realist painter Gustave Courbet, bristling from being rejected by the Exposition Universelle, went out on his own and created the independent "Pavilion of Realism," a temporary structure he erected next door to the official venue. Nineteen years later, a group of young French rebels exhibited their paintings in the storefront that had been Nadar's photographic studio. The first group to exhibit outside the academic domain, the rebels were dubbed the Impressionists that year.

Artists have curated exhibitions in alternative spaces ever since. Think of the 1913 Armory Show that introduced avant-garde Modernism to the United States, which was organized by American painters Arthur B. Davies, Walter Kuhn, and Walter Pach. Or think about the New York Society of Independent Artists that committed to show any artworks submitted. (Marcel Duchamp resigned from the group when they refused to display his "Fountain" of 1917.) Or think, more recently, of the excellent series of exhibitions organized by sculptor John O'Brien in the Brewery.

This weekend, two groups of artists continued that fine tradition by presenting exhibitions in alternative spaces, one a private home, the other a storefront that serves, primarily, as a center for photographic education

Pretty Vacant

The home show was titled "Pretty Vacant" and organized by artist Yvette Gellis. When two of her friends decided to radically remodel the interior of their Westwood home, Gellis suggested that they invite artists to install works in each of the many rooms before demolition began. Thirteen artists were included in the show: Joshua Aster, Kristin Calabrese, Walpa D'Mark, Martin Durazo, Mark Dutcher, Chuck Feesago, Michol Hebron, Kelly McLane, Megan Madzoeff, Constance Mallinson, Jared Pankin, Christopher Pate, Eve Wood, and Alexis Zoto.

As with most large group exhibitions, "Pretty Vacant" was variously successful. Gellis's reworking of the living room was stunning. She created large, gestural paintings on the walls, on the wall-to-wall carpeting, and on large plexi panels angled throughout the interior. The space was transformed into a handsome dripped-and-poured Abstract Expressionist masterpiece.

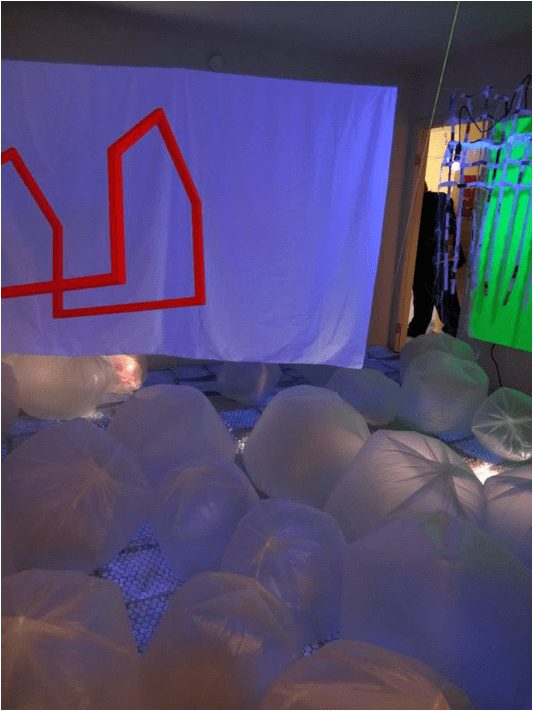

Chuck Feesago used a room at the top of the stairs, lining the floor with air-filled plastic bags illumined by flashing neon lights. Bisecting the room was glowing wall of fabric, in front of which was suspended fragile red house form. Feesago's room had two doors. The doorway nearest the stairs was flanked by a poem written in silhouetted words against a smudged graphite cloud, "Uncertainty/It is a landscape of questionable belief/fueled by anxiety." Around the corner, the second doorway was hung with one of Feesago's poured grids. The entire space was alternatively lit by green, then purple, then pearly white lights. A disco-flashing, rhythmically pulsating house heart.

Constance Mallinson went through the house to remove squares of wallpaper and floor covering. She transformed all the squares into painting surfaces and hung them in one of the bedrooms. She collaged on some, painted on others, and left still others blank, allowing viewers to see them as "ready-made" artworks a la Duchamp. One of Mallinson's "assisted ready-mades" was a pale rectangle of aged wallpaper. On it, she painted four rippled tulips, allowing their petals and leaves to drip and run down the textured paper's surface. Gorgeous.

Other artists repurposed parts of the house or hung their paintings on the empty walls or installed videos against the bathroom mirrors. (I watched one video through a shower stall, while drinking a shot of tequila that was--I was assured--part of the installation.)

Of course, other artists have taken condemned dwellings and transformed them. Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro famously turned an abandoned Hollywood home into Womanhouse in 1972. A major icon of feminist art history, Womanhouse allowed artists to transform rooms into installations (Chicago's "Menstruation Bathroom" was probably most notorious) and enact domestic-themed performances (Faith Wilding's poetically evocative "Waiting").

More than forty years later, artists are still taking Los Angeles area homes and turning them into evocative spaces for Post Modern artworks. They are also following in the footsteps of the Impressionists, using alternative photographic spaces for curatorial projects.

Art and Cake

A Contemporary Art Magazine with a Focus on the Los Angeles Art Scene

Biomythography: Currency Exchange Opens at Claremont

By Jacqueline Bell Johnson

September 7, 2016

Biomythography: Currency Exchange at Claremont. Photo credit- Jacqueline Bell Johnson, All rights reserved

Biomythography: Currency Exchange

Curated by Chris Christion and Jessica Wimbley

Currency Exchange is the third in a series of Biomythography exhibitions co-curated by Jessica Wimbley and Chris Christion. The show includes artists from southern California as well as several emerging artists from Costa Rica. The term biomythography was coined by warrior poet Audre Lorde; it means “combining elements of history, biography, and myth.” This concept is the springboard for the exhibitions and offers the artists a “richer language in articulating and contextualizing their work.”

The idea to explore it as a curatorial project came from a lecture Wimbley gave at Chapman. “The term really resonated with the class, which lead me to believe there is something to biomythography and its relation to visual arts.”

The artworks in the show all have a sense of self portrait, but much deeper than that, as if you are viewing the generations of familial past of that person. These works are a visual storytelling, relaying past experiences, exaggerating/removing/including details to alter context for relevance. They are a parallel to passing down history orally. And as in oral tradition, these explorations evolve into myth and legend, though the outcome remains sincere.

Biomythography: Currency Exchange at Claremont. Photo credit- Jessica Wimbly, All rights reserved

Marton Robinson’s Untitled 2016 is a painting made with chalkboard paint and chalk, directly on the wall of the gallery. The deep matte black paint sinks into the wall creating a vortex, implying depth that pulls you into the doorway of the painting. The chalk drawing on top is a mix of imagery: indigenous African people and wallpaper-style scrolls and flourishes surround an image of Madonna and child, portrayed as African. Underneath is written “El Negrito: Productos Esotericos Y Reli….” (That last word is obstructed by figure, but my guess is “Reliquias”). Translation- The Black: esoteric products and relics. The phrase reads as an advertisement, souring the beauty of the image.

I remember/I return is a series of works by Elisa Bergel Melo. Two are included in this show, a video and collection of photos. The group of black and white photos hung at different depths from the gallery wall, some of the photographs casting shadows. The imagery is altered. Scenes from childhood visually skip and repeat within the photographs. The shadows create gray and black rectangles on the wall, visible among the photos. They act as place holders for memories out of grasp. The accompanying video piece presents similar imagery drifting in and out of abstraction in real time.

Glen Wilson’s Broken Record series is of items that anyone could find while taking a stroll down a neighborhood street. They are formally displayed as more as evidence than artifact. Close by is Wilson’s chain-link sculpture, the fence gates hung like street signs from an aluminum pole that goes all the way to the ceiling. Shredded photographs are revived by being woven into the chain-link, scenes perhaps from that same walk. The use of the gates play with your access to the imagery, acting as both barrier and support. The images themselves are of sun-drenched people in daily-life scenes in the city.

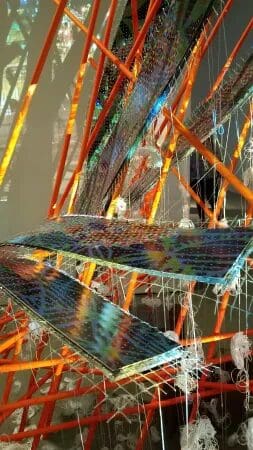

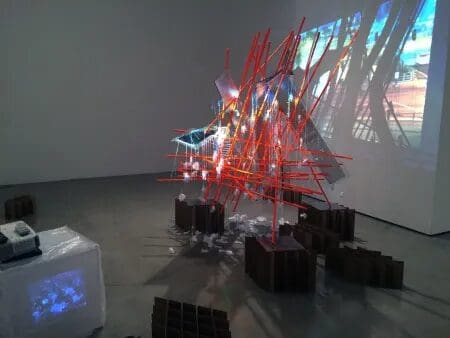

FILTER by Chuck Feesago is a multimedia presentation: a sculpture of orange sticks, string, iridescent silver paper, and cardboard -all made kinetic by the projection of night traffic passing through to the wall behind the piece. The form has an architectural logic to it, with its weight placed on cardboard blocks creating a clearance underneath. It has a sense of a camp or child’s fort and encouraging attempts to walk through it (as many gallery goers tried to do). The sculpture glitters in the light of the video, its angled lines in between erecting and collapsing. The city scape is always in flux and us Angelinos will be witnessing a lot more growth skyward now revisions to restrictions have been made. In the context of this show, FILTER represents the larger-than-life feel living in a highly condescended, ever growing, sea of lights and ads environment the city scape is, and the nostalgia that is generated for the past when we view the new. The piece also hints at the consequences of those bright lights: tucked away along the side is a small projection of an outdoor scene cropped by palm trees an ode to something that was lost.

Los Angeles Times

Art Just Off the Freeway

By Kirk Silsbee

May 17, 2013

Lincoln Avenue just north of the roaring Foothill (210) Freeway is a residential street where cars barrel up and down the road. In front of a gated building that sits off the street, a small sign discreetly reads: “off ramp gallery — contemporary art in a historic home.” It’s where Charles Alexander and Jane Chafin live and host their home gallery, the Off Ramp.

Past the gate, the roomy house with a mid-century modern feel has lots of right angles and warm, dark woods. Alexander, a recently retired architect, explains that the Off Ramp is open to the public Fridays through Sundays from 1 to 5 p.m. “We will take people,” he offers, “in the week, but by appointment only.”

Alexander and Chafin met in New York and shared a love of art and design. “I’m a minimalist,” he points out, “and Jane is much more expressive in her tastes.” She adds: “We both like well-crafted things. I come from a conceptual art background but I also like the visual.”

They’ve had this gallery for five years now, with eight artists in their stable, including collagist Lou Beach, sculptor Nicholette Kominos and painter Patssi Valdez.

“We can never guess which shows will make money,” he continues. “Some shows don’t sell anything and some others we make money on, to our great surprise. But we’ve stayed open for five years, and it’s been a real journey for us.” Chafin adds, “We wouldn’t be able to do this if the only consideration was the bottom line.”

The home was built by a movie studio cabinetmaker for his dancer wife, Evelyn LeMone; it was the site of her Pasadena Dance Theatre. High ceilings and clerestory lighting give a sense of openness to the space. Some large, spinous sculptures by Kominos bring to mind some of Louise Bourgeois’ arachnid figures. In the Guest Room, three very different post-modern expressions sit together: Chuck Freesago’s large tapestry of acrylic on gloss paper and bubble wrap, Valdez’s enveloping interior painting, and four painterly color photos by Anita Bunn.

Last December, Chafin invited Valdez to decorate the living room for the season. Valdez, who came out of the innovative ASCO conceptual collective from East Los Angeles, works in several mediums.

“Patssi came in,” Chafin excitedly recalls, “and she used large papers that she had painted. She cut them and twisted and folded them and arranged them around the room in ways I’d never seen before. It was very festive and she made the room into a visual party.”

The vibrant hot and cool colors of the interior painting, “The Green Room” (2000), convey a controlled Expressionism. From her home in L.A., Valdez explains, “I paint the room the way it feels, not the way it looks. My color sense comes from a very strong emotional place, a very deep place. Sometimes the only way I can express those emotions is through color.”

“I’ve been doing other things,” Valdez says. “Painting ceramics, working with fabrics — crafty things. I did a show with Jane last year, a whole group of works on paper, and I really enjoyed doing that.”

The ASCO retrospective that bowed at LACMA in 2011 opens in Mexico soon and Valdez will accompany it. “It seems so long ago that we did that work,” she sighs. “And I’m in a transition now; I want to move into something new but I don’t know what will inspire me. I’m hoping that the travel will show me new things and new directions.”

Exhibition of the artists Anita Bunn, Chuck Feesago, Patssi Valdez

Off Ramp Gallery, 1702 Lincoln Ave., Pasadena.

University of La Verne Campus Times

Pacific Island Artists Capture Culture

Robert Penalber

May 4, 2012

Rosanna Raymond poses for a picture taken by her friend Chantal Fraser on Saturday in the Harris Gallery. Both women are featured artists in “ATA: An Exhibition of Contemporary Samoan Art,” which focuses on the present by taking the essence of Samoan culture and incorporating it into a contemporary dialogue. / photo by Christian Uriarte

Artists of the Pacific Islands gathered in LaFetra Hall to present their work as part of the opening day for the Contemporary Samoan Art Exhibition.

The all-day event included films, poetry, visual performing arts and a discussion panel before opening the Harris Gallery exhibition to the public.

“I was trying to put it together because, in a sense, I was so alone,” art studio manager Chuck Feesago said. “There are very few artists out there, let alone Samoan.”

Feesago said he was able to connect with Pacific Island artists through Facebook and wanted to connect as much as he could to build a sense of community.

“It was very inspiring knowing there are people out there,” Feesago said.

The artists were interested in exhibiting their work in response to American misperceptions of Oceania in tiki kitsch caused by tourism.

Curator and artist Dan Taulapapa McMullin began the event by playing short films from Samoan filmmakers.

New Zealand filmmaker Anna Breckon’s “Rebecca2” was the feature film.

The film follows Kate, played by artist Daniel Satele, as a married woman in New Zealand who becomes disheveled by the suicide of iconic actress Rebecca.

Years later, Kate is still so affected by the celebrity’s death that she has now become an alcoholic, compulsive masturbator and unemployed mess.

Encouraged by the wisdom of her television set, Kate sets off on a journey of self-improvement and pursues the mystery of Rebecca’s supposed death.

Chamorro filmmaker Alex Munoz’s documentary short “Born Fo Bang” was one of the more inspiring pieces.

The film tells the story of Joey, a youth at the Hawaii Youth Correctional Facility.

Joey is hoping to leave the gang his brother forced him into and make it to college.

“Born Fo Bang” was filmed at the Hawaii Youth Correctional Facility and each role was played by the respective teenagers incarcerated there.

“I thought the film was the most relatable and emotional,” UC Riverside student Jazmin Castro said.

U.S. Samoan actor-playwright Napoleon Tavale performed his one-person work “Inoa Fanau (Birth of a Name),” based on the story behind his name.

After singing the national anthem for Samoa, Tavale demanded the attention of his audience through his dramatic acting in the story of abuse.

Associate professor of psychology Felicia Beardsley was moderator of a discussion panel of eight artists.

“For the first time, we’re all actually going to have a conversation,” Feesago said.

The artists shared their motivations behind their art pieces.

“Through the arts, it brought me back to where I came from,” filmmaker Sila Agavale said. “At a young age in Samoa we all start with performance arts from religion.”

“Growing up, my dad would tell us all these stories,” performer Rosanna Raymond said. “So I think it has a huge influence on the films I do today.”

The artists discussed Samoan tradition and how it has been modernized.

“There’s a huge influence from Hollywood,” Tavale said. “They have a bigger platform than Samoan culture.”

Feesago agreed and said that stereotypical symbols and motifs of Samoan culture have led to culture being commoditized.

“I struggle constantly with the frameworks for what we’ve been taught,” storyteller Amelia Niumeitolu said. “We have our own vernacular, own abstracts, own vocabulary.”

“I can only speak for myself and the stories I tell,” Raymond said. “I have to be true to myself, and that is being a Pacific Islander. And it is a struggle, but also a blessing.”